Here's the second half of my Favorite Albums of 2015 list (Part One is here). Before we start, here's a playlist featuring one track from each of the 50 albums I wrote about. You can listen to it in order, on shuffle, whatever, follow your heart.

25.

Errors

Lease of Life

Errors are signed to Mogwai’s record label and have toured with both Chvrches and Underworld, to give you an idea of the circles they run in. Somewhere between Mogwai’s post-rock, Karl Hyde’s techno and krautrock, and Chvrches laser-guided synth pop is Lease of Life. The Scottish trio have been slowly shifting away from guitars and towards synths throughout their career, but there’s still a sense of spontaneity throughout, sections that you would call jams or solos if the members were playing Gibsons instead of the Korg synthesizers they acquired for the making of their fourth album. The playfulness and overt 80s throwback of Cut Copy’s Zonoscope is the reference point I keep thinking about, but none of the influences, as real as they are, do the album’s individuality justice. It’s out there in its own little world, nestled amongst some of the giants of the 80s and today, very much near them and but not within them.

|

24.

Title Fight

Hyperview

23.

Deafheaven

New Bermuda

22.

Beach Slang

The Things We Do To Find People Who Feel Like Us

21.

Sleater-Kinney

No Cities To Love

20.

American Wrestlers

American Wrestlers

American Wrestlers, contrary to what the name implies, consists of only one person, and he is not American. Scottish musician Gary McClure recorded the project's debut album on an eight track after leaving his former band and moving from Manchester to St. Louis to marry his then-girlfriend, and it certainly sounds like it was done by one person on an eight track, from the lo-fi fuzz to the sleepy drum machine to the ambient background hum. But it's a quietly beautiful, heartfelt record, strewn with memorable guitar riffs and melodies that linger. Opener "There's No One Crying Over Me Either" provides the high point, raising the stakes with a piercing guitar solo halfway through, then easing into a piano-driven outro as McClure sings "I want it but I need it like the hole in my head / if the hip kids buy in," laying the song gently to rest. The squawking guitar solo on "Kelly" cuts through the hissing static like a lightning bolt, while "Cheapshot," which wouldn't be out of place on the first couple Built To Spill records, seemingly revels in the poor sound quality, layering on buzz and static around the guitar riffs for the added weight. At times you find yourself wondering how great these songs could be if properly recorded by a full band, but it's possible that some of the magic comes from their humble origins.

Alabama Shakes

Sound & Color

Sound &Color is, uh, really good. Going back and listening to the first album after hearing the second, as I did, is jarring; not only is the first sorely underwritten by comparison, the difference in production is huge. Boys & Girls sounds oddly muted and kinda thin--frankly, it sounds like it was recorded 60 years ago with low-quality equipment and then played through an FM radio--while Sound & Color is fat like a Zeppelin record. Opener “Sound & Color” shimmers to life with a gorgeous bass and marimba duet that slowly swells with Howard’s transcendent voice, here kept just in check. She fully unloads on the next song, album highlight “Don’t Wanna Fight,” which rides a bouncy contender for “riff of the year” straight into a sustained, high-pitched half-yowl from Howard. “Gimme All Your Love” is the kind of organ-heavy slow jam (that eventually turns into a loud jam) you can’t help but imagine hearing coming from a festival stage, probably at Bonnaroo, likely from My Morning Jacket. There’s really no one else who could deliver it like Howard, though, not even Jim James, easily slipping between soulful croon and full-throated roar. On the first album, she and the rest of the extremely capable band sounded like talented musicians in search of worthy songs; on Sound & Color, they’ve found them.

18.

Courtney Barnett

Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit

"Put me on a pedestal and I'll only disappoint you!" Courtney Barnett sings gleefully on "Pedestrian At Best," the riotous lead single from the Australian musician's debut studio album. The tongue-in-cheek warning made sense coming from Barnett, whose previous releases, two excellent EPs eventually combined into The Double EP: A Season of Split Peas, gathered an excess of hype for someone like Barnett, who sings in a lazy drawl that moves easily between melody and spoken word, and ruminates on mundane observations and details from the world around her, as well as general nonsense ("Give me all your money / and I'll make some origami, honey.") The problem with her message was that it came on a track as exciting as "Pedestrian At Best," introduced by squealing feedback, and propelled by a crashing syncopated riff and Barnett's stream-of-consciousness delivery that, here, is equal parts singing and rapping. She again tries to sell herself short: "I must confess, I've made a mess / of what should be a small success / but I digress, at least I tried my very best, I guess," to no avail.

The album's beating heart comes on "Depreston," which takes Barnett's throw-away inner-monologue observations and finds the profundity in them, carried by a gentle riff reminiscent of Wilco's "One Sunday Morning." Barnett goes house shopping in Preston, and can't help noticing small things in the home--"a handrail in the shower / a collection of those canisters for coffee, tea, and flour / and a photo of a young man in a van in Vietnam,"--and is overwhelmed imagining the deceased, former resident ("And I wonder what she bought it for").

Down the street from me, an elderly woman passed away earlier this year. As I understand it, she had grown close to a younger woman on our street, who comforted her in the months leading up to her death, and her son decided that his mom would have wanted her new friend to have the house that they had spent those last months bonding in, that she would appreciate it, and it wasn't like he needed or wanted it. It was an older house, on the edge of a hill that ran down to a creek. I think about that house when I listen to "Depreston," and the line Barnett and her band repeat at the end of the song: "If you've got a spare half a million / you could knock it down, and start rebuilding." Evidently, its new owner did have a spare half a million, because she knocked the house down in a few days and started rebuilding. The new home looks much nicer.

17.

Wax Idols

American Tragic

16.

Viet Cong

Viet Cong

Viet Cong hide moments of brilliant beauty inside clouds of synthesizer and effects pedal-created noise. On “March of Progress,” distorted, blown-out drums cascade repeatedly like artillery strikes over a simple chord change for close to 3 minutes before anything else happens. Eventually, droning voices chime in and the melody that was previously carried by the drums switches to a koto or heavily altered harpsichord-like synth sample. Then suddenly, everything drops except for a drone and a bass drum, before the clouds part, the sun shines through, and the song barrels to its conclusion in double-time. It’s an astonishing first listen, and remains powerful dozens of iterations later. The album is filled with moments like that (though none that resonate on quite that level), of building dissonance and distortion so that when (or if) that moment of melodic clarity comes, it releases all of that pent-up noise and musical angst. “Continental Shelf” takes a guitar riff as big as its name and marches violently through the verses to reach a chorus that resolves the hanging tension with a beautiful half-step guitar slide. Despite the vast number of clear reference points, from a previous (similar but distinct) incarnation of several members as Women, to the bold, garish pop of Wolf Parade, to the foundations of post-punk laid down by Joy Division and Bauhaus, Viet Cong manage to land firmly on the side of “influenced by,” as opposed to “ripping off,” through the synthesis of various elements of each into a new whole.

About the name: the band had a show at Oberlin College cancelled, with organizers citing concerns that the name was insensitive to Vietnamese-Americans students and communities. The band had previously said “it’s just a band name. It’s just what we called ourselves.” They eventually released a statement in which they acknowledged that the name was a bad example of appropriation and announced plans to change it to something else TBA, because “We are a band who want to make music and play our music for our fans. We are not here to cause pain or remind people of atrocities of the past.” I imagine they felt the name conveyed the harsh, sometimes violent quality their music at times possesses (and maybe they took one too many cues from Joy Division), but in any case, it’s a mature reaction from a band that will hopefully continue to make music, under some name.

15.

Speedy Ortiz

Foil Deer

I heard Sadie Dupuis' line "We were the law school rejects / so we quarreled at the bar instead," right about the same time I read my rejection letter from my first choice law school, so the runners-up anthem "The Graduates" holds a bit of extra meaning for me. "I was the best being second place," Dupuis sings, bemused. Her lyrics run slightly abstract, like Stephen Malkmus with a poetry MFA--which, okay, Dupuis does have a poetry MFA, and has toured with Malkmus before, so it's an easy leap--but where Pavement songs were often apathetic ramblings, Dupuis largely throws around threats: "Don't ever touch my ring you fool / you'll be cursed for a lifetime," "I've known you not so very long but watch your back / because baby's so good with a blade." On "Raising the Skate" she vents her frustration at the double-standard allowed for women: either don't take full credit for your accomplishments, or do and risk being called 'bossy' or worse. "I'm not bossy, I'm the boss," she says defiantly, "so if you wanna row, you'd best have an awfully big boat." The haunting "My Dead Girl," however, vaguely recounts an incident where Dupuis, locked in her car in essentially the middle of nowhere, was threatened by a group of men, banging on the windows and 'joking' about pulling her out. "If these are my last words, guess you found me," she sings, weary of the world women are forced to deal with. "Now I'm the dead girl you wanted." The song--and the album, in whole--speak to, as Dupis said in the interview, "the simultaneous freedom to be whatever you want, to do whatever you want, coupled with the unfortunate reality that there’s always someone trying to take that power away from you." It's a weighty sentiment, deftly conveyed.

14.

Majical Cloudz

Are You Alone?

13.

Lower Dens

Escape From Evil

Escape From Evil sounds like it’s running from something. On their third album, Lower Dens fully embrace the dark synth pop palette of bands like Chromatics or Beach House, though replacing the latter’s sleepy drum machine with an actual drummer does wonders for the album’s energy levels. That energy is always there; even on slower-paced songs, there’s a restless unease that seeps through and propels them forwards. Jana Hunter’s delivery is quietly mesmerizing and the biggest reason why this album doesn’t fade after the novelty of the clean guitar or synth hooks wear off, as do many other electro pop albums.

If all you were interested in were hooks, you would not leave disappointed. The staccato melody that drives “To Die in L.A.” is as good as any this year, but it’s continually Hunter’s vocal lines that stay with you: the falsetto plea of “I will treat you better,” on “Ondine” is breathtaking; the way Hunter holds the last syllable of “Time will turn the tide” on the chorus of “To Die in L.A.” as the band surges to life around it never gets old; the entirety of “Company” is absolutely spell-binding. The song opens with a driving bass line and Hunter’s admission “I wish I could feel anything at all,” before a stunning extended vocal run that double or triple-tracks Hunter’s voice and adds delays to turn it into an ominous crowd of voices seemingly reenacting “Comfortably Numb”: “Come right in and sit beside the fire / we’ll have someone bring you a tray of pigs in blankets, you look / really uncomfortable if I’m being honest / pale. Did you hit something on your way over?” “They’ll know just what to do / in fact, I think they’ve seen this kind of thing before / Don’t worry, relax, you’ll be fine / Just lie back and stop squirming.” “Please listen to us / we have your best interests in mind / we’ve had our eye on you for a long time.” “Babe hush, now this won’t hurt at all.” It’s the high point of the album and typifies the unsettled forward motion that Lower Dens bottled and turned into what should be their breakthrough effort.

12.

The Amazing

Picture You

11.

Fred Thomas

All Are Saved

10.

Jamie xx

In Color

When I first heard “Gosh,” the opening track on Jamie Smith’s debut solo release that follows a spotless career filled with collaborations, remixes, and multiple The xx albums (and when I say “spotless,” I mean there is not a bad song with the name Jamie xx attached to it), I was driving home from work around 9:00 p.m., streaming the song from BBC Radio 1, after seeing tweets that Jamie xx had debuted the song with them earlier that evening. At first, I was nonplussed. I was used to more subtle builds from Jamie xx, tracks that were more synth-heavy than drum-heavy, and this opened with a gigantic, pulsing bass note, off-beat percussion, and a dancehall “oh my gosh” vocal sample. More layers kept adding on but they were still all rhythmic, not melodic. It was very un-Jamie, as I knew him. It was cool, but, not what I expected from him. I was almost disappointed, but...almost two minutes in, a bassline. The perfect chord progression. It was like it had been there all along, if I had listened to it. A whistle, growing in volume, descending from the heavens, that turned into a beautiful, glorious synth melody. It explored every facet of its lower registers before ascending back into the stratosphere, reaching piercing, otherworldly levels. And then, it was gone. The song dissolved into that bass note and some brief snappets of dialogue. It was literally jaw-dropping. My jaw hung open as I drove down through those dark, rolling hills.

On the album, “Sleep Sound,” follows, and it helps resettle you after the transcendent experience that is “Gosh.” This is what you expect from Jamie xx; this is vintage Jamie xx. It was actually released in 2014, along with album closer “Girl,” but it’s as good as ever, with its perfect two-step chord-progression, driving bass, expertly-applied low-pass filters, and that “yeah” vocal sample over the drops. “Obvs” is also what you expect from Jamie xx: an inexplicable infatuation with steel drums justified by his masterful application of them. “Loud Places” pairs a brilliant sample of Idris Muhammed’s “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” with Smith’s The xx bandmate Romy to dazzling results: “I go to loud places / to find someone / to be quiet with,” she sings, as the song explores that loud-quiet dichotomy with deceptive ease, becoming one of the few tracks extolling the importance and impact of club-going that actually feels convincing.

If Nicolas Jaar’s distinguishing strength (at least on Nymphs) is his percussion and the myriad ways he uses it to carry a song, Jamie Smith’s is his use of vocal samples, and closer “Girl” is an exhibition of that talent. It’s a delightful slow-burner with one weakness: the track it has to follow. “The Rest Is Noise” claims similar airspace as “Gosh,” pulling in a police siren to carry its melody, and reaching for that same moment on the dancefloor when, late in the evening--probably closer to morning--the simple combination of rhythm and melody becomes all-consuming. There are no vocal samples beyond softly-sung “ooh”s here; handclaps, synths, and syncopated bass drums carry it to the stars. All you have, at that moment, is the music and the emotions it stirs in you. That blocks out everything else. The rest becomes noise.

9.

All Dogs

Kicking Every Day

The heart of All Dogs’ excellent debut album comes after three tracks of relentless self-critique from singer Maryn Jones. On opener “Black Hole,” “there’s a shaking underneath my skin.../ I am a black hole / everything I touch slowly turns to dust.” On “How Long” she wonders “when all this unrest becomes part of marrow in my bones / where to put it? / Only you will let me in when I’m tearing off my skin.” And then “Sunday Morning” finds her pleading “And if I’m on the floor can you make sure I’m alright?” and admitting her shortcomings: “and I only said I wanted to be kind / but I never said I’d have the will to try.” That’s all within the first 11 minutes, and Jones starts to carry on this line of thinking on “That Kind of Girl,” which opens with the admission “And I know that I am always fucking up your world,” until a third party advises the subject that they’re “better off not messing with that kind of girl,” at which point the guitars take on a new, growling weight and Jones’ voice a new edge: “What’s that mean? / Stay away from me.” It’s a dramatic lyrical turn and a relatable one: everyone expects to be their own worst critic, but when someone else joins in calling you a fuckup, the response is naturally “Well, what the fuck do you know about me?”

8.

Nicolas Jaar

Nymphs I, II, III, IV

That I’m stretching the rules this fragrantly to include these four EPs (the first of which was initially released in 2011 and reissued last month through his own label Other People) should tell you something about just how good they are. In a year that saw him release film scores, remixes, and collaborations, Jaar found time for his first solo releases since, well, the original release of Nymphs I in 2011 as the Don’t Break My Love EP. Taken as one work, the EPs’ seven tracks run 53 minutes, and cement Jaar alongside Burial as the best ambient/minimalist electronic producers working today. “Don’t Break My Love” finds Jaar skittering through a simple descending keyboard pattern with his typical active and varied percussion section and sparse vocal samples, all of which builds for nearly five minutes to a climactic moment of silence, before he drops the actual hook of the song, sung through distorted, pitch-shifted vocals, and jams on it for the song’s final minute. Its Nymphs I counterpart, “Why Didn’t You Save Me,” is structured essentially the same, and it demonstrates one of Jaar’s hidden strengths, which is the way he teases and sometimes carries melodies and often the bulk of a track’s musical ideas and progression through his percussion library, which has to be as big as anyone’s.

On Nymphs II, “The Three Sides of Audrey and Why She’s All Alone Now ” evokes a landscape viewed through a time-lapse video that keeps breaking up, stuttering and glitching back and forth, in and out of place as clouds and their shadows slide over mountain tops, as the seasons change and storms come and go. Then, four minutes in, a snare rings out, there’s a brief scream, and thunderous syncopated bass drums kick the listener out of their reverie. Vocals and synths creep back in, the drums drop, the same snare pattern teases the same drop and...nothing. The clouds roll back over, the vocal samples keep gliding in and out. A third time, the snare, and this time, the beat resumes but more thoughtful, carrying the melody now, and not for long. Jaar’s voice cuts in, rain starts falling, and the meditation resumes. It’s a journey of a track.

“No One is Looking At U,” “Swim,” and “Fight,” by contrast, almost feel like traditional deep house dance tracks, which is to say, in Jaar's deft hands they’re among the best dance tracks released this year. But part of their effect comes from the way that Jaar makes extended time spent grooving on one of his immaculate beats feel like a privilege and an unknown quantity. With him, grooves come and go, carried away like leaves on the wind. When he lets them linger, it’s special, and all three of these tracks are a treasure. Collectively, the Nymphs projects represent electronic music at its most immersive.

7.

Oneohtrix Point Never

Garden of Delete

For all the side material Daniel Lopatin released to accompany Garden of Delete--videos, blogs, fake Twitter accounts, even a fake band (Kaoss Edge) who make music of a fake genre ("hypergrunge")--the album art really is the best descriptor of this complex record. Look at it. There are so many lines drawn, jittery but straight, disconnected but interwoven, nonsensical but forming multiple shapes at once. A rose in a vase? A bird perched on a tree stump? A burning torch? It could be anything or it could be nothing.

This is an electronic album that is neither ambient or danceable, though it is very much capital-E Experimental. You won't nod your head much in listening, but there are nods to big-tent EDM, metal's chugging guitar riffs, MIDI-based video game music, and flamenco guitars. It rewards headphone listening, not just because of the vast array of soundscapes Lopatin paints with painstaking detail, but also because playing it on speakers risks anyone else within earshot giving you a weird look and asking "What is this?" What it is is one of the most unique listening experiences of the year, an album that defies description and rewards exploration.

6.

Protomartyr

The Agent Intellect

"I'm going out in style," Joe Casey sneers on "Cowards Starve." A trap a number of bands taking style cues from 80s post-punk have fallen into is forgetting to bring any substance with them to match. Protomartyr does not fall into this trap. Casey's lyrics deal with devils and demons, literal and figurative, and the evil that lurks in mundanity. Opener "The Devil in his Youth" paints Lucifer as a disaffected suburban teenager, who "grew up pale and healthy / with the blessings of his father," but "it all changed when he came of age / It was nothing like the simulated game / the women didn't love him." Casey howls over racing guitars "You will feel the way I do / You'll hurt the way I do," in his delivery that is not quite singing, though it occasionally flirts with melody. "Boyce or Boice" warns against devils seeking to corrupt you from within your electronics, as described by The End-Times Deliverance Center. "Pontiac 87" describes a riot outside a stadium in Pontiac, Michigan, following a visit and speech from the Pope ("Old folks turned brutish / trampling their way out the gates / towards Heaven").

Casey's parents both died as The Agent Intellect was being written, his father to a heart attack and his mother to Alzheimer's. The darkly brooding "Why Does It Shake" recounts his mother's struggle, who at first declares "Sharp mind, eternal youth / I'll be the first to never die...I'm never gonna lose it," then later despairs "Why does it shake? The body, the body, the body, the body," as Greg Ahee's guitar screams like a banshee and Alex Leonard's tom pattern ticks like a clock. There is, however, amidst all the darkness and despair, a moment of shimmering light. "Ellen," named for Casey's mother (and possibly written from the perspective of his father), is as beautiful a piece of music as any made this year, played with grace and restraint by a band capable of burning a song to ash, and Casey's simple lyrics. "Beneath the shade / I will wait / For Ellen...I'll pass the time / with our memories / For Ellen." The song ends quietly, only for the band to reprise it for one final chorus, as if Casey simply couldn't let her go quite yet.

5.

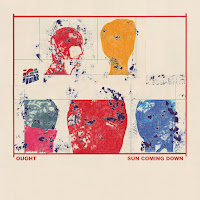

Ought

Sun Coming Down

I didn’t hear Ought’s 2014 debut album, More Than Any Other Day, until after I had already finished my Favorite Albums of 2014 list, so let me state here, for the record: More Than Any Other Day would have been my 4th favorite album had I heard it in time (and Todd Terje would be the new number 5, as of today). Similar to Sun Coming Down, More Than Any Other Day pairs four solid, noisy post-punk exercises with four transcendent tracks. “Today, More Than Any Other Day” is an absolutely crucial anthem about overcoming depression to find the strength to go shopping for groceries and interact with other people like a normal, functional human; “Habit” is up there with Lou Reed’s “Heroin” as one of the best songs about drug addiction (“And is there something you were trying to express? / It’s not that you need it / It’s that you need it.”), and throws “Heroin” a nod with the dissonant strings that buzz nervously overhead on the outro. “The Weather Song” is propelled to greater heights by Tim Keen’s rapidfire drumming and singer Tim Darcy’s shouts of “I! Just wanna revel in your lies” on the chorus. And “Forgiveness” is the comedown from that exhilarating four-song run, with Darcy moaning over sustained organ chords and that same “Heroin” violin screech.

Sun Coming Down is also eight songs, three brilliant, five quite good. Opener “Men For Miles” is Ought at their frantic best, harsh guitar noise resolving in unexpected directions and Darcy’s vocals covering as much territory as possible. “Passionate Turn” stumbles its way into a beautiful, accelerating ballad, featuring wonderful melodic mirroring between Darcy’s vocal line and the lead guitar, and perfect drumming from Keen, whose playing and overall drum tone (equal parts Keen and production) is among my favorites this year: inventive and active playing, full, fat, balanced tone. Album--and possibly 2015--highlight “Beautiful Blue Sky” is the natural progression of “Today More Than Any Other Day,” with Darcy reeling off a list of small-talk subjects (“How’s the family? / How’s your health been? / Fancy seeing you here / Beautiful weather today / How’s the church? / How’s your job?”) with his David Byrne sing-song delivery, repeating each phrase over and over again until it loses meaning, like when you write a word out over and over until it looks made-up, or at least misspelled. Where “Today More Than Other Day” found Darcy building himself up on mundane activities, using them as small steps out of the pit he’d dug, here they are driving him mad. “I am no longer afraid to die / cause that is all that I have left / Yes,” he says, drawing out the final word with relish. The song itself is built on a simple two-chord-progression that’s not too far from “Marquee Moon”’s, but it makes the absolute most of it, at once haunting and glorious, triumphant and unsettled. “That’s all that we have,” Darcy says, of the maddening mundane talking points, “just this, and the big beautiful blue sky.”

A lot of of post-punk and post-punk-indebted music are dissonant, noisy, restless sort of songs where the point is to hang that chord resolution within earshot but just out of reach, sometimes ignoring it, sometimes teasing it, sometimes ultimately embracing it. Ought do this very well; so too do Viet Cong and Protomartyr, to name others on this list. Beyond the inherent merit in the tension of that dissonance, the resolution has that much more impact when it fills that void created for it. Ought have created two records in two years, uneven and a little rough around the edges, that nevertheless display real mastery of their craft and contain some of the most gorgeous, life-affirming moments of music of the year.

4.

Kendrick Lamar

To Pimp A Butterfly

Here’s the thing: I’m a white dude who doesn’t listen to all that much rap, as you can infer from the appearance of just two rap albums on this list, in a year that I am told was a banner year for hip-hop. I also don’t have too extensive a background in many of the sounds that influenced this record--jazz, funk, soul, r&b--and I both take issue with respectability politics in general (ie, “What about black-on-black crime?”), which comprises an unfortunate amount of Kendrick’s racial commentary here (“So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the streets / when gangbanging made me kill a n---a blacker than me”), and also feel a little uncomfortable criticizing a black person for their approach to racial commentary. So.

With all of those caveats in mind, I still think this is the Album of the Year, in the sense that it is the most impressive, ambitious, interesting, meaningful album released this year that I’ve heard or heard of. That’s not precisely what this list is trying to measure, so it isn’t the final album I’m going to talk about here. But it’s damn close.

There’s just so much to unpack and talk about on this album. One of the amazing things about To Pimp A Butterfly is that it came out in March and Music Twitter stays getting into arguments about it. There was a period there where you couldn’t swing a George Clinton sample without hitting another TPAB thinkpiece. I don’t really want to toss my hat into that ring; I’d rather direct you to kris ex’s powerful words, who has said the final words that really need to be said about it. So, I’m just going to mention a few parts of this album I enjoyed:

The way “These Walls” opens, with a woodwind wail that morphs into a moaning female voice, as chants of “if these walls could talk” rise around her until a husky voice says, simply, “sex” into the silence, before the soulful beat drops.

The way “King Kunta,” predicted the Drake Ghostwriting Thing (“I can dig rapping / but a rapper with a ghostwriter? / What the fuck happened? / Oh no! / I swore I wouldn’t tell!”), in addition to having just the sickest bass line, in addition to the way it truncates the vocal sample on the chorus (“Oh yeah!”), cutting it off just before the voice finishes yelling, in addition to the “we want the funk!” outro, in addition to just being a fucking jam and a half.

The way the free jazz mental breakdown of “u,” is never an easy listen, because of how difficult it must have been to make in the first place. The way Kendrick yelps “Loving you is complicated!” at himself.

The way “Alright” opens with a sample of voices singing a four-part jazz chord played like a keyboard chord over Kendrick’s proclamation “All’s my life I had to fight!” and an aimless saxophone solo, before suddenly they lock into rhythm, Kendrick drops The Line (“I’m fucked up homie / you fucked up / but if god got us, then we gon’ be alright!”) as the drum fill brings in just the biggest, baddest beat.

The way the whole album sounds. It’s just wonderful; rich, luscious, full. Immaculate. You can get lost in the thinkpieces and the societal importance and the chants of “We gon’ be alright!” at police brutality protests, and all of that is worth discussing and even getting lost in, but you can also just get lost in the sounds this album throws at you. It’s not an easy listen, but it sure is a powerful one.

3.

Titus Andronicus

The Most Lamentable Tragedy

When Titus Andronicus announced that their new album would be a 90 minute, 29 track, ostensibly fictional rock opera inspired by lead singer Patrick Stickles’ experience with manic depression, it felt like it could only be either a masterpiece or a trainwreck. What we got was a trainwreck of a masterpiece, the beautiful, glorious, ear-splitting, sound of a man whose best and worst tendencies collided with destructive, brilliant force. The album plays like a series of manic episodes, building and racing with feverish speed, punctuated by the depressive lulls that always must follow. You wonder whether an album this reckless, furious, and ambitious could have been created without a manic episode, but it certainly couldn’t have been created by anyone other than Stickles. It should be noted that the entire band plays their hearts out on The Most Lamentable Tragedy and deserve full credit; in particular, drummer Eric Harm’s ability to match Stickles’ frantic pace is instrumental on tracks like “Dimed Out,” and Elio DeLuca’s piano playing on “I Lost My Mind (+@),” “Lonely Boy,” and “Fatal Flaw” lend the tracks a deranged-E-Street-Band feel (not to mention Ryan Weisheit’s squealing saxophone solo on “Lonely Boy”).

There’s a career’s worth of hooks and riffs on this album, for a band with one of the new millennium's great guitar albums already to their name (2010’s The Monitor). At times, it’s an exhausting, overwhelming listen. There’s so much here, so many ideas; in some ways, it’s the rock equivalent of To Pimp A Butterfly in its overstuffed, hyperbolic nature, and the way that its shortcomings are the result of its unwavering artistic ambition. It’s a world-conquering album, which finds it at odds with the world, because guitar albums don’t conquer the world anymore. On the terrific “Fired Up,” Stickles sings to this point: “Believe me, you gotta believe in a dumb dream / even if seeing the death of a dumb dream / makes a man mean / mean, mean, real mean / that’s what you gotta be.”

2.

Hop Along

Painted Shut

"The world's gotten so small and embarrassing," shouts Frances Quinlan on "Waitress," recounting the experience of seeing an ex and his new girlfriend walk into the restaurant she worked at, and the way her counterpart looked at her, Quinlan mortified at what she must think of her. Beyond the sheer beauty of the line itself, is the way Quinlan sings it, and the rest of the album. Her voice carries a touch of Nashville and a punch of rock, frequently fraying around its edges, contorting into different shapes, ranging from breathy lows to breathtaking highs. It's the vocal performance of the year (Alabama Shakes' Brittany Howard would be the runner-up) and that alone would be enough to keep you coming back.

Painted Shut was produced by John Agnello, who has worked with Sonic Youth, The Hold Steady, Kurt Vile, Andrew W.K., and Social Distortion, to name a few. Here he takes the raw energy of their debut, Get Disowned, and adds weight and volume to songs that spin around themselves, building and growing--or maybe I just feel that way about them because I'm so used to turning the volume up every few seconds whenever I listen to this album.

There's so many wonderful moments here; I would be remiss if I didn't mention the way Quinlan sings "Who is gonna talk trash long after I'm gone?" that just wrecks me every time I hear it. But the still center of Painted Shut is the acoustic ballad "Happy to See Me," just Quinlan's guitar and singular voice. Near the end she daydreams "On the train home I am hoping / that I get to be very old / And when I'm old I'll only see people from my past / and they all will be happy to see me / We all will remember things the same," and repeats the last line over and over, chewing it up and spitting it out with different inflections each time, stripping her voice raw and screaming herself hoarse. It's mesmerizing.

1.

The World Is A Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid To Die

Harmlessness

If you didn’t know better, you might think The World Is A Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid To Die were an alternate timeline Arcade Fire (circa 2004-2005): a shifting ensemble of band members that number closer to ten than five, guitars paired with string instruments, multiple vocalists, and stadium-sized ambition. Here’s the big difference: Arcade Fire were “indie” in the mid-00s, which was the best time to be an indie band. The World Is… are “emo” a decade later, at a time in which being called emo is more of a mixed bag.

On the one hand, the term “emo” is just recently no longer being used purely as a pejorative for the kinds of bands your younger brother liked in middle school. On the other hand, major outlets are still slow to cover (or, to be precise, praise) bands like The World Is... or The Hotelier or Joyce Manor or You Blew It! or Restorations or Foxing or Modern Baseball or Into It. Over It. or any other band whose reach extends about as far as the adoring crowds at FEST. As former The World Is… member Greg Horbal said to Ian Cohen in an interview, “There is no way we’ll ever be put on the same show as Parquet Courts,” (whose Andrew Savage was in pop-punk band Teenage Cool Kids before he was in Parquet Courts) who Horbal correctly uses as shorthand for “critic-accepted guitar band,” AKA, an indie rock band.

In the same interview current The World Is… guitarist Derrick Shanholtzer-Dvorak notes that the band was initially termed “post-emo” and that’s really the best label for them, if we have to have one (and we don’t, really, but when there’s a billion bands doing a million things out there, it helps to have some words to use to talk about them). And if there’s to be a flagship album for post-emo, it can’t be anything other than Harmlessness, which takes a handful of the trappings of pop-punk-indebted emo and adds Funeral-era-indie ambition and instrumentation, and post-rock scope and song structures, and winds up with a somewhat messy, slightly overstuffed, truly great 53 minutes of guitar music.

Like To Pimp A Butterfly and The Most Lamentable Tragedy, where Harmlessness suffers, it does so because of its ambition. Album highlight “January 10th, 2014” tells the story of Diana, the Hunter of Bus Drivers, an unknown woman from Juarez, Mexico who killed two bus drivers in retaliation for an epidemic of otherwise unpunished sexual assaults by bus drivers on female passengers returning from factory shifts late at night. Many of the song’s lyrics are taken straight from the This American Life episode about her, and there’s a moment where nominal lead vocalist David Bello and vocalist/keyboardist Katie Shanholtzer-Dvorak reenact an exchange from the article (“Are you Diana, the Hunter / Are you afraid of me now? / Well yeah, shouldn't I be?”) that comes across with all the grace of a teenaged art project.

But if it works, it works, and everything here does, ultimately. One of the reasons “emo” became taboo among critics (and yeah, I’m projecting here) was that it reminded them of when they were teens and had “bad taste” and jammed to The Promise Ring and Jimmy Eat World and Sunny Day Real Estate every day; thank god they grew out of that and discovered Pavement, right? Harmlessness takes that youthful feeling of unashamed exuberance and runs with it further than anyone has yet, and the album’s occasional moments of lyrical awkwardness come from an uninhibited spirit that makes the rest of the album so liberating and wonderful. Even the drumming follows this pattern; Steven Buttery is tremendous throughout the album, though he has a tendency to overplay slightly, which is distracting at times, but it comes across as a result of how damn excited he is by this music that he just can’t help but play everything he’s capable of.

As much as the Kendrick album is probably the Album of the Year, in terms of impact and “what album do we still talk about in 10 years,” Harmlessness feels almost as capital-I Important, in that this really could be (and should be) the last time we have to have this kind of discussion about emo and indie and why they’re perceived differently. This is an album that matches the communal-catharsis-heights as Arcade Fire, the instrumental beauty of Sigur Rós, the crescendo rock of Godspeed You! or Mogwai--hell, “Haircuts for Everybody” exists solely to build tension for a minute and a half so that it can release it in a minute and a half climax. This an album that would defy classification if not for the scene the people behind it came out of, the kinds of shows they get booked to, and the kinds of publications that champion them. This is an album that wants to conquer the world and knows it won’t, but goddamn does it try.

No comments:

Post a Comment